While walking down a quiet street in Korakuen one night, Tokyo-based photographer Cody Ellingham was struck by the discordance of the structures he saw. On one side, the "hypermodern, illuminated theme park" of Tokyo Dome, and on the other, a dilapidated danchi building.

This contrast was the start of a year-long exploration into the world of danchi: Japan's public housing apartments. Built as part of post-war recovery as a symbol of modernity and hope, danchi are now decaying. His work has culminated in a two-day exhibition of photography exploring the danchi of today, in all their glory—albeit former.

A step away from the fire-prone wooden houses of most communities, the towering concrete creatures were built to cope with the rapidly expanding urban populations. They were more than just homes though; they embodied entire communities, with shops, playgrounds and even schools in some of the bigger complexes. Back then, the future was concrete: danchi reflected the post-war dream of modernity and were hailed as a visual symbol of development, progress and permanence. As Ellingham describes it: "Superstition and Shinto were replaced by television and consumerism."

Of course, nothing spells decay like a vision of the future, and danchi were no different. As Ellingham explored over 40 complexes, he found the clusters of identical buildings offered a Kafkaesque version of community, where each household could live the same life, the signs of their existence nothing but transient markers easily removed, ready for the next inhabitant.

The dream was not lost, however, as he discovered upon delving into these communities. The transient impression of personality was challenged by community centres still running, art murals decorating stark walls and playgrounds still in use. Balancing the existence of the original dream, which remains unchanged despite the adapting surroundings, is tough: the hope that "tomorrow will be better than yesterday" is the faint hope Ellingham saw in the remaining concrete communities.

The Japanese concept of mono no aware is one Ellingham links strongly to the world of danchi. Often translated as the "pathos of existence", it refers to a recognition of the impermeable nature and transience of things. Danchi are a perfect example, as not only will their physical existence soon be forgotten as they fall foul of earthquake regulations and relentless property development, the dreams they once represented will vanish too. As Ellingham reflects: "You cannot see the dream of an afternoon danchi with the sounds of laughter without hinting at the abandoned structures they will one day become."

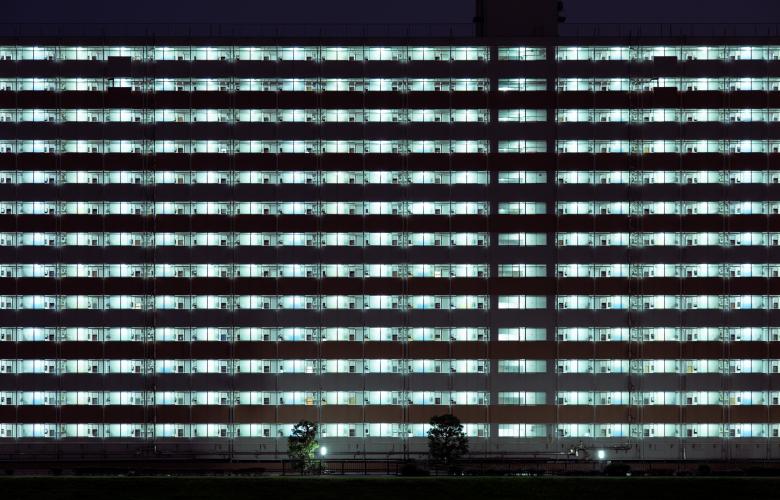

Choosing to photograph the buildings at night, Ellingham wanted to evoke the concept of dreaming and to create the iconic visual images of the finished display. A "row of windows illuminated from the inside, only hinting at the existence of people" was expressive of the struggle of danchi as a whole.

Having started as an aesthetic interest, the project developed as Ellingham explored more and more properties and discussed it with mentors. The three subjects of the exhibition are Dreams, Decline and Decay—and the social and historical implications of the buildings soon became apparent. Once visited by royalty and hailed as the future, today they house immigrants and the elderly, with small rooms and no modern elevators. Leaving a nostalgia Ellingham feels is hard to associate with: danchi represent the dreams, decline and decay simultaneously — a standing monument to times gone by.

Born in New Zealand, Ellingham is now based in Tokyo and photographs the city extensively. Having previously gained notoriety for his Derive series, depicting futurist Japanese cityscapes, this project looks back to an alternative version of the future.

By Lily Crossley-Baxter

Similar to this:

Florian Busch and the floating stadium: A futuristic Olympic insight

Out with the old, in with the new: Why older buildings are unpopular in Japan

How to be a good neighbour in Japan