As I write this on the roof terrace of my architectural studio, embraced by Shibuya’s crescent skyscrapers, the ambient hum composed of neighborhood traffic, birds chirping and snippets of laughter from nearby streets and schoolyards is suddenly displaced by the rolling thunder of two low-flying, wide-body commercial jets, descending precariously on a catastrophic collision course with nearby high-rise towers.

Barely illusory, the scene is a poignant reminder of Tokyo’s two relatively recent aviation near-catastrophes. It also beckons the question of how prime real estate in Tokyo “branded” neighborhoods can be irrevocably subjected to profound threats to quality of life and value.

Flying the north “approach”, or landing path to Tokyo International Airport at Haneda, an interminable parade of “heavy” airliners originating from as far away as North America, Europe, Southeast Asia, as well as various major cities in Japan are on descent to barely 2200ft (670m) over Shibuya City’s busy streets and famously crowded Hachiko crossing, skimming 1400ft (426m) above Scramble Square’s observation platform in the heart of the populous CBD. 1

In as little as 2-minute intervals at speeds of 200mph, engines screaming to compensate for the heavy drag of lowered flaps, extended landing gear and speed brakes, giant aircraft roar just 1900ft (580m) over Hiroo’s bustling cafes and popular shops, Arisugawa Park’s quaint duck pond and crowded playgrounds, as well as Minami-Azabu’s swanky three-story homes and roof terraces where conversation, both outside and within is interrupted or rendered inaudible by the deafening roar. Seconds further on, the French Embassy with its manicured gardens, pool, and outdoor entertaining areas for visiting dignitaries and guests is not spared from the blanket of noise.

Onwards, just meters away, the jets continue their full-throated descent over Kisato University’s campus, Shirogane Elementary and High School’s buildings and grounds, and exclusive private schools and kindergartens nearby. As the jumbo jets advance in loud descent, the entire up-market Shirogane neighborhood is inundated by the raucous din as airliners boom onwards, dropping to 1100ft (335m) over Tennozu’s popular riverside cafes and parks on their relentless march towards Tokyo International Airport, barely 4 miles away.

The drama is not over.

At touchdown the deafening roar of enormous pairs of jet engines, slammed into reverse-thrust echoes back across city neighborhoods already shattered by the thunderous clamor, paused only briefly until the cacophonous cycle repeats itself.

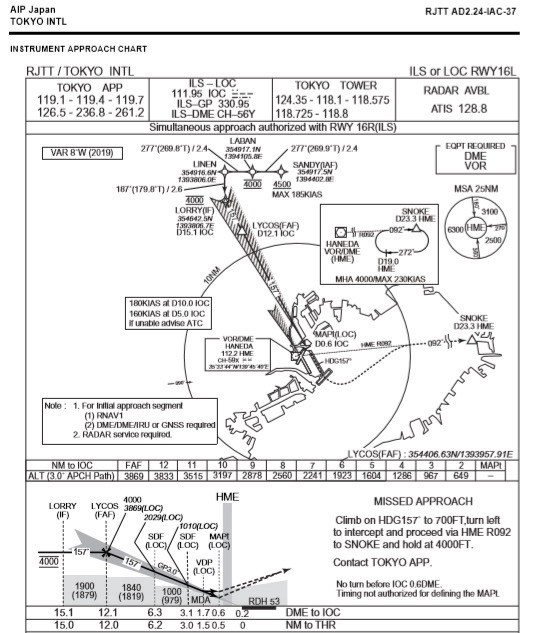

On prescribed 3-degree glide-slopes extended over central Tokyo’s eastern high-end neighborhoods, wide-body jumbo commercial airliners are flying the ILS or LOC approaches to runways 16L (Left) or 16R (Right) at Haneda. 2

Residents stop walking and look up at the sky. Apartment dwellers hear the roar while indoors with the windows closed. A woman in her 60s “had a feeling of oppression” and laments: “I will not be able to open the windows because of the noise. I am worried that my lifestyle will change.” 3

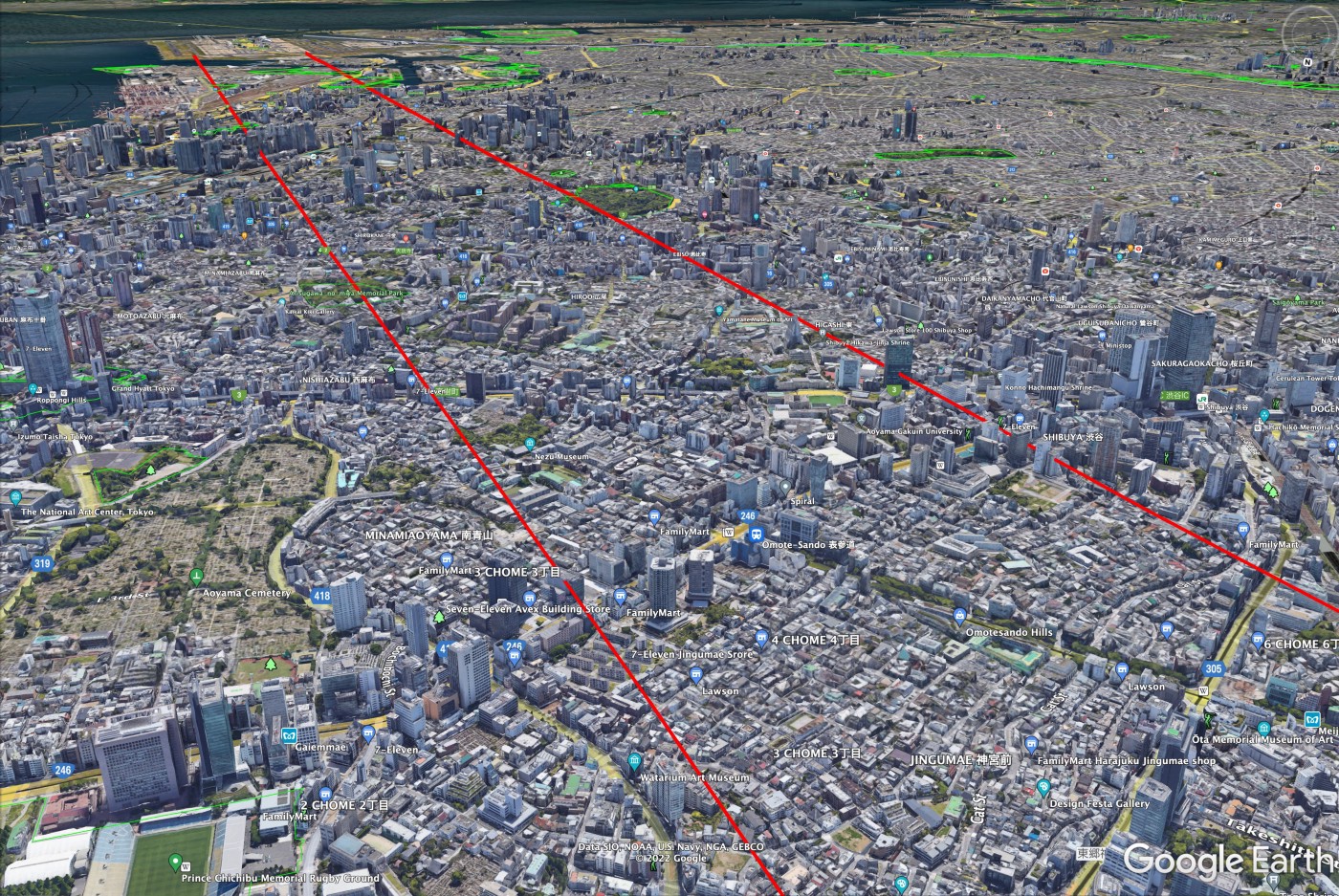

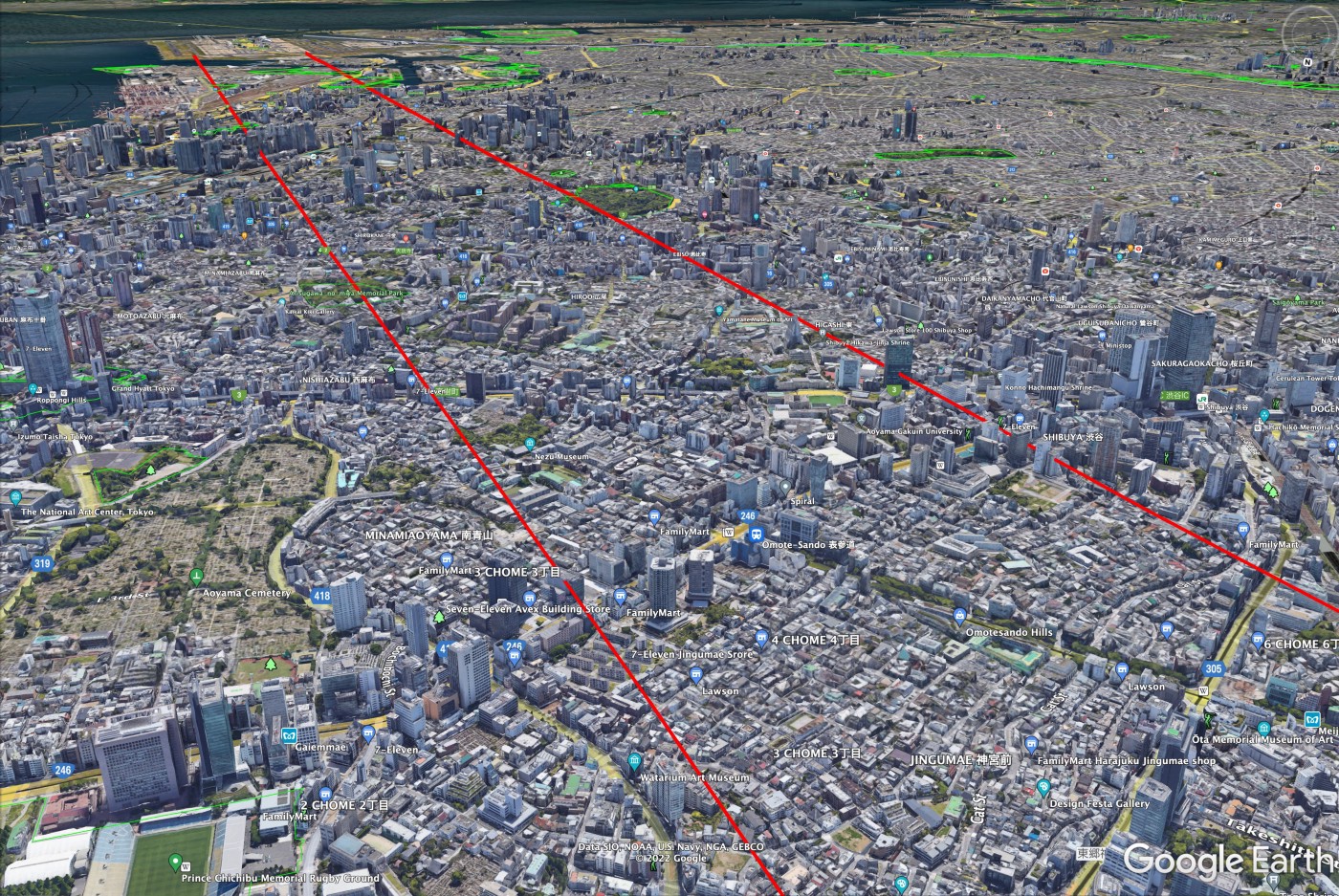

Ground tracks (red lines) for the ILS, LOC and RNAV approaches to Haneda’s runways 16L and 16R, directly over Shibuya and Tokyo’s prime districts of Minami-Aoyama, Nishi-Azabu, Minami-Azabu, Hiroo, Shirokane, and finally the towers of Takanawa and Shinagawa just short of the runway thresholds. (Google Earth, Author)

MLIT (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transportation and Tourism) studies show aircraft noise levels increase from 70 decibels (dB) to at least 80dB between Shibuya, Shinagawa Ward and Tennozu. On low overcast or cloudy days when ILS approaches are typically flown, the roar of jet engines is further amplified by reflection from cloud bases. Exposure to 80dB for prolonged periods of time (several hours in a day) is harmful. How harmful? 85dB is generally considered damaging to human hearing, and the US EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) recommends limiting exposure to noise levels above 70dB over a 24-hour period to prevent hearing loss. 4

44 landings per hour

In response to anticipated additional airline arrivals for Tokyo’s 2020 Olympics, new low altitude landing routes, or “approaches” in aviation parlance, were added by MLIT in March 2020 to boost (by 44 landings per hour) the capacity of Tokyo International Airport, supplementing existing approaches from the east and over Tokyo Bay from the south. While an obvious, if not contentious solution, the proposed approaches from the north and west over the Shinjuku and Shibuya CBDs could not be pursued without cooperation and agreement of the ultimate governors of Tokyo City’s relevant airspace: the US Department of Defense.

Since the immediate post-war period, much of the airspace in Japan is controlled by the US military, formalized with the Japanese government under the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA). The “Yakota Airspace” covers western-Tokyo and facilitates US military aircraft operations across the city and frequent helicopter traffic to the US Army’s Hardy Barracks helipad in central Tokyo’s’ Roppongi.

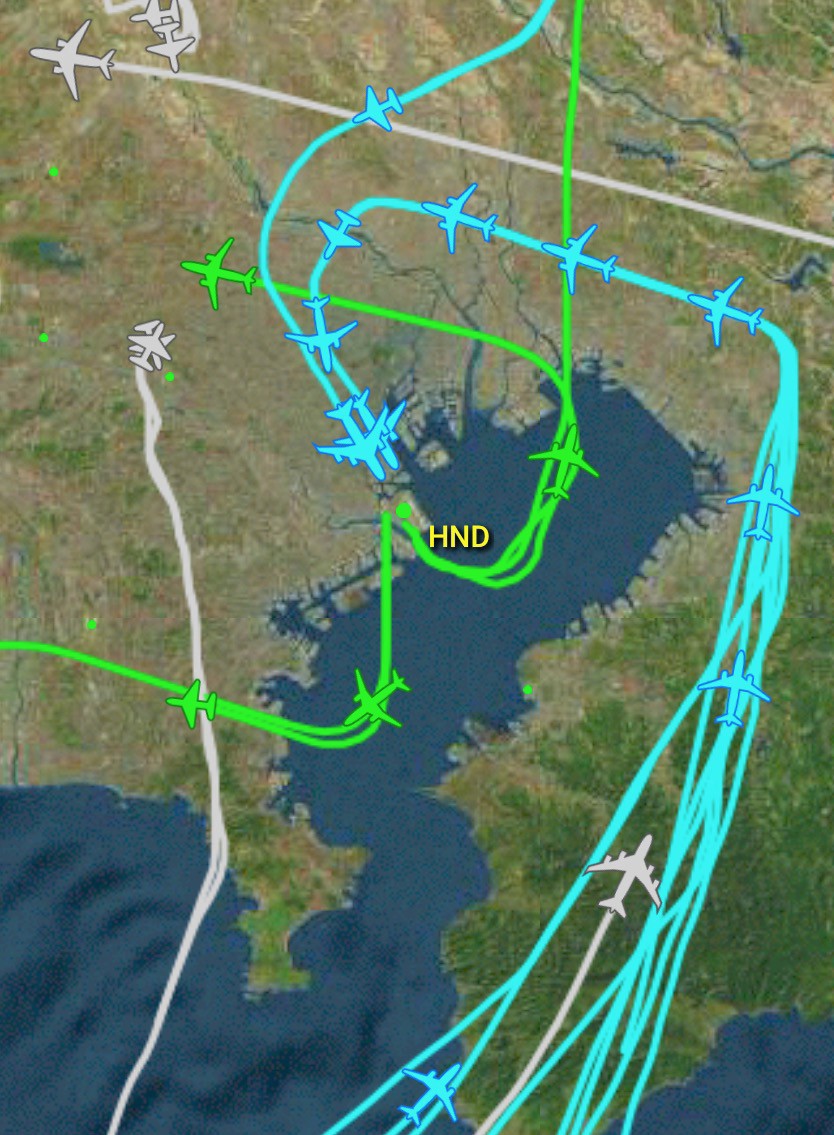

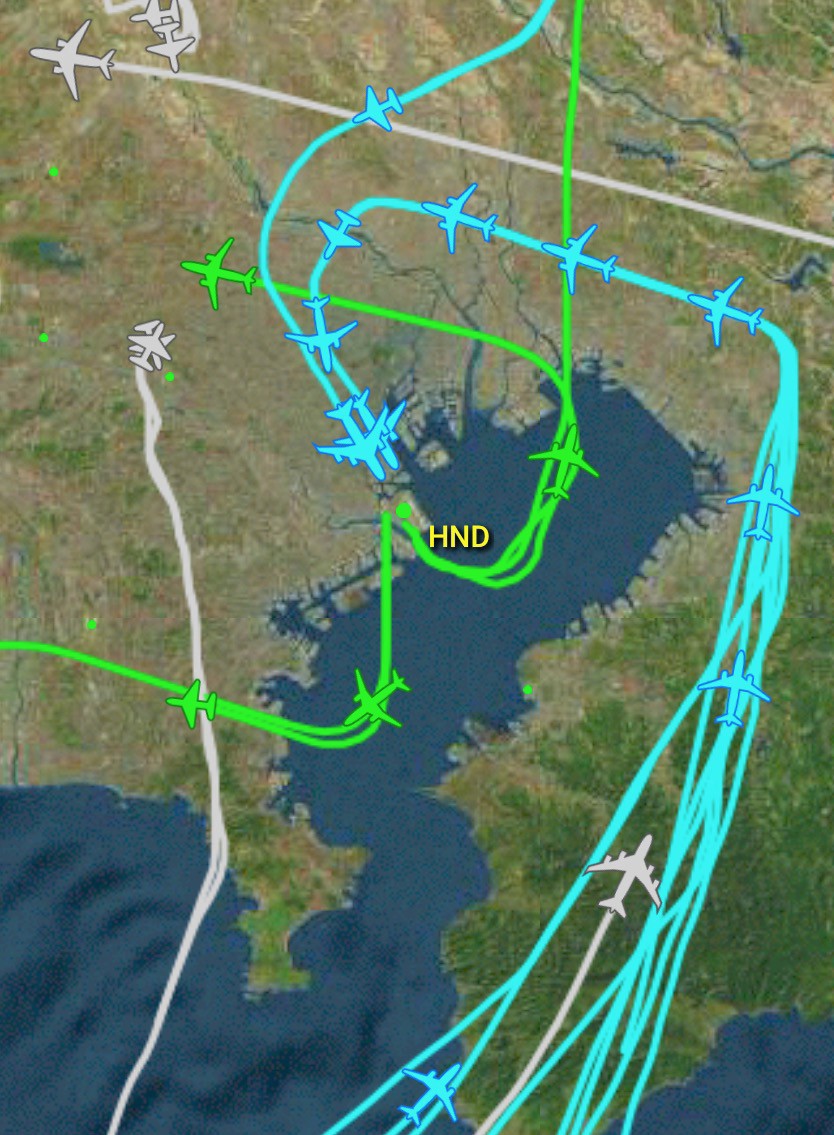

International and domestic airliners arriving (magenta tracks) from multiple directions maneuvering over Tokyo City for the ILS, LOC and RNAV approaches to Haneda’s (HND) runways 16L and 16R. Operations (grey tracks) over the US Military Yakota Airbase can be seen to the west. (FlightAware)

Pilots flying north-western ILS approaches to Haneda Airport must enter the Yakota Airspace for the initial segment of their approach before leaving it over the JR Nakano Station, about a mile north-west of Shinjuku. To minimize this inconvenience to US Military airspace controllers and enable US forces “to fly as many aircraft as possible in their [central Tokyo city] airspace for training and other purposes”, additional approach paths with a steeper glide-slope were recently adopted by the Japanese government. 5

Called “RNAV (Radar or Area Navigation) approach”, this procedure for aircraft arriving from the west involves an abnormally steep glide slope of 3.45 degrees (the standard is 3 degrees), starting from a higher altitude closer-in to the airport. Understandably, pilots consider this “acute” glide-slope a riskier procedure as it demands faster air speeds, quicker control inputs and higher probabilities of triggering “sink rate” and “glide slope” cockpit alarms and warnings, all of which add further distraction to pilots already burdened by the high demands of cockpit management during the most critical phase of flight: the landing.

Exacerbating this challenge, and the focus required to follow the Instrument Approach Chart precisely is nearby air traffic, both civilian and military, at unforgivingly low altitudes over heavily populated areas studded with skyscrapers and radio towers.

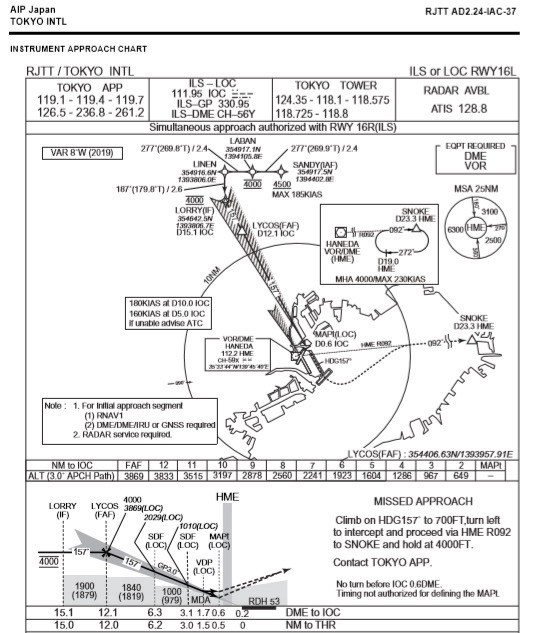

Instrument Approach Chart used by IFR pilots for the ILS or LOC approach to Tokyo International Airport Runway 16L (Left) at Haneda. Altitudes are in Feet ASL (Above Sea Level) and distances from the runway threshold (THR) are in Miles. Note the 10NM (Nautical Mile) ring. Arisugawa Park and the French Embassy in Minami-Azabu on the approach course are just over halfway, at about 5.5NM. (AIP Japan)

Near Crashes

Pilot error and mechanical failure in modern aviation are rare. But either, especially in combination can lead to a cascade of events that too often result in catastrophe.

Pilot error is most prevalent in complex landing operations close to the ground. Flying into airports located within dense urban environments, especially if flying non-standard, complex approach procedures such as those described above pose an existential threat to passengers and crew as well as people and property on the ground. Tokyo’s expansive built environment, complex mix of US military and Japanese civilian airspace and Haneda’s dense runway configuration are catalysts for pilot misjudgment. This is exemplified by two relatively recent near crashes (“serious incidents” in MLIT restrained official-speak) in Tokyo.

On April 11, 2018, Thai Airways flight THA/TG660, a 747–400 (“Jumbo Jet”) with 384 passengers and crew arrived over Tokyo after a five-hour flight from Bangkok. The pilot in command was on approach to Tokyo International Airport runway 16L when, in the heat of complex pre-landing checks, control inputs and tower communications, coupled with poor cockpit crew management in the final moments of the instrument approach, the pilot erroneously flew entirely off-course and lost sight of the runway. The subsequent dangerously steep descent set off “Obstacle, Obstacle, Pull-Up!” alarms at 434ft (132m), followed by the “TOO LOW TERRAIN” alarm at 304ft (93m). In the confusion that followed, the jumbo jet dropped to within 282ft. (93m) of the surface and 0.24 nautical miles (445m) of the 230ft (70m)-high Tokyo Bayside Wind Power Plant. In extreme peril, the pilot in command immediately “maneuvered an emergency operation to avoid crash into the ground”, pulled-up sharply and commenced a go-around to an entirely different runway. 6

MLIT’s investigation concluded that pilot error (cockpit crew mismanagement) put all passengers and crew in danger. This is to say nothing of the danger posed to persons and property on the ground.

Some years earlier on September 19, 2004, while attempting to land at Tokyo Haneda Airport, a 747–200 jumbo jet chartered by Orient Thai Airways veered off course due to the pilots’ lack of familiarity with airports’ approach procedures. The aircraft subsequently continued flight at low-level, crossing over Tokyo Station and the Nihonbashi district at 1770ft (540m) and strayed within 660ft (200m), or about 1 ½ times the length of a home run, of the tip of Tokyo Tower, the city’s 1090ft (333m) tall landmark. The plane eventually made a successful landing at Haneda Airport.7

Inexplicably, the pilot was only suspended, and flight crew required to undergo retraining.

A passenger jet flies by Tokyo Tower (Tatsuya Shimada)

Flightpaths and Property Values

The catastrophic consequences of pilot error, or mechanical failure to aircraft flying so low over a densely populated city, studded with skyscrapers taller than half the altitude of the approach paths gives pause, if not cause for alarm. Such legitimate concerns are compounded by noise and pollution impacts that further diminish the safety and quality of life for residents, workers, and visitors within the swaths of urban fabric underlying the western approach paths.

Low approaches are not uncommon over urban or suburban areas. It is perhaps more common for unregulated residential development to progressively encroach airports under the final approach path. Urban sprawl colliding with, so to speak, airport expansion in the modern era is a classic symptom of rapid economic growth in the developed world.

Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) is an example of this uneasy coexistence. On the extreme edge of Santa Monica Bay, the east-west runways are oriented perpendicular to the ocean which lies to the west. The most frequently used approach paths start overland from the east, exploiting the preponderance of offshore breezes and headwinds, with final descent above narrow corridors of suburban fabric below.8

In this real-world case-study, the relationship between property values, socio-economic demography, quality of life and the vertical separation from the approach glide-slope is as common sense would dictate — the noisier the location, the cheaper (more affordable) the property values. Low-income residential areas progressively give way in a linear manner to industry, commerce, and ultimately vast expanses of rental car and long-term parking lots directly under the final approach path.

In the case of Los Angeles, the realpolitik of geographic, socio-economic stratification closely correlates to racial and ethnic aggregation. The presence of the airport has been the principal catalyst for the city’s population movements and arguably the de-facto racial segregation of its environs, most poignantly directly under LAX’s principal approach paths.

Not so in Tokyo, at least not yet.

As described earlier, the new western approach paths to runways 16 Left and Right at Tokyo International Airport travel directly over some of the city’s most desirable and expensive districts (wards), with tall office and hotel towers along much of the ground track right up to about 3 miles (5 kilometers) from the runway thresholds. Clustered in-between are tightly packed neighborhoods of single-family, detached residences, schools, and pocket parks.

Mid and high-rise buildings are typically (but not always) hermetically sealed and acoustically isolated, and less vulnerable to noise and air pollution from “heavy” jets passing close overhead. Such construction is not feasible (nor allowed) for typical residential buildings, most of which, in the seriously affected areas are single-family, detached homes of two to four stories, and of various ages of construction.

Tokyo’s more gentrified districts such as Nishi-azabu, Hiroo, Arisugawa, Minami-Azabu, Shirogane are traditionally much sought-after locations, with a gravitational pull for expensive amenities such as private international schools and hospitals, as well as exclusive recreation facilities, all of which has conferred on these neighborhoods a “branded” status. Property prices are consequently amongst the highest in the city.

Zoning restrictions have been formulated to protect the “low-density” character of these central-city branded neighborhoods, made up of typically small lots of 180–200m2 area, with a maximum of only 60% coverage (footprint) allowable and a 10 meter height restriction. The affordability equation, driven primarily by location and land price equates to very expensive 450–500m2 homes, most often equipped with a wide range of deluxe amenities, affordable only to the highest echelons of Tokyo’s socio-economic spectrum.

And, paradoxically, with increasing regularity, they mostly lie under a blanket of jet noise and avgas exhaust.

Noise levels, inside as well as out, spur complaints from residents of Minami-Azabu’s up-scale neighborhoods. (Shogo Koshida)

As a case-study, the homes my architecture practice has designed in these areas are all constructed in reinforced concrete (the structure of choice for longevity and mortgage finance-reasons), with double glazing as standard and oodles of insulation, notwithstanding Tokyo’s relatively temperate climate.

To maximize the utility of every square centimeter of very expensive land, as well as the finite buildable area allowed by zoning controls, balconies are discouraged, but roof terraces readily accessed from living spaces are an essential (and typically the only) open space amenity. The terraces, typically with excellent city views, more than double the usable area for entertaining and relaxation without busting the zoning code that strictly limits buildable GFA, and makes typically suburban, usable ground level gardens and recreational backyards an economic impossibility.

And yet, during the times that the low western approach flightpaths are active, which is typically afternoons through early evening, relaxation (let alone conversation) at these outdoor spaces becomes interrupted to the point of impractical.

Inside, notwithstanding substantial concrete plus stud wall thickness, insulated roofs and double-glazed windows, the cyclical din of descending aircraft just overhead is highly noticeable, distracting, in certain circumstances embarrassing; not at all what you would expect in new homes of US$10–20million value.

With fair weather enjoyment of outdoor spaces seriously impaired, and noise levels inside ranging from irritating to downright annoying, real estate agents no doubt avoid showings during periods when the troublesome approaches are active.

Arisugawa Park, a highly prized and cleverly designed public recreation space steeped in local history, together with an adjacent tennis club traditionally frequented by the Imperial family, is “ground-zero” for many of these branded neighborhoods. Like all open spaces under the flight path the park, and its racket of rambunctious birds, ducks and kids at play is rendered far less pleasant when dominated, at regular intervals by the loud engine whine of low-flying, wide-bodied jets passing just overhead.

Private schools and hospitals as well as public community institutions fare worse than private residences. Construction budgets for these buildings typically prohibit the degree of noise isolation that even high-end, multi-family residences can afford. To make matters worse, schools and community buildings are generally fully occupied and operational during the hours that the low, western approach corridors are commonly flown.

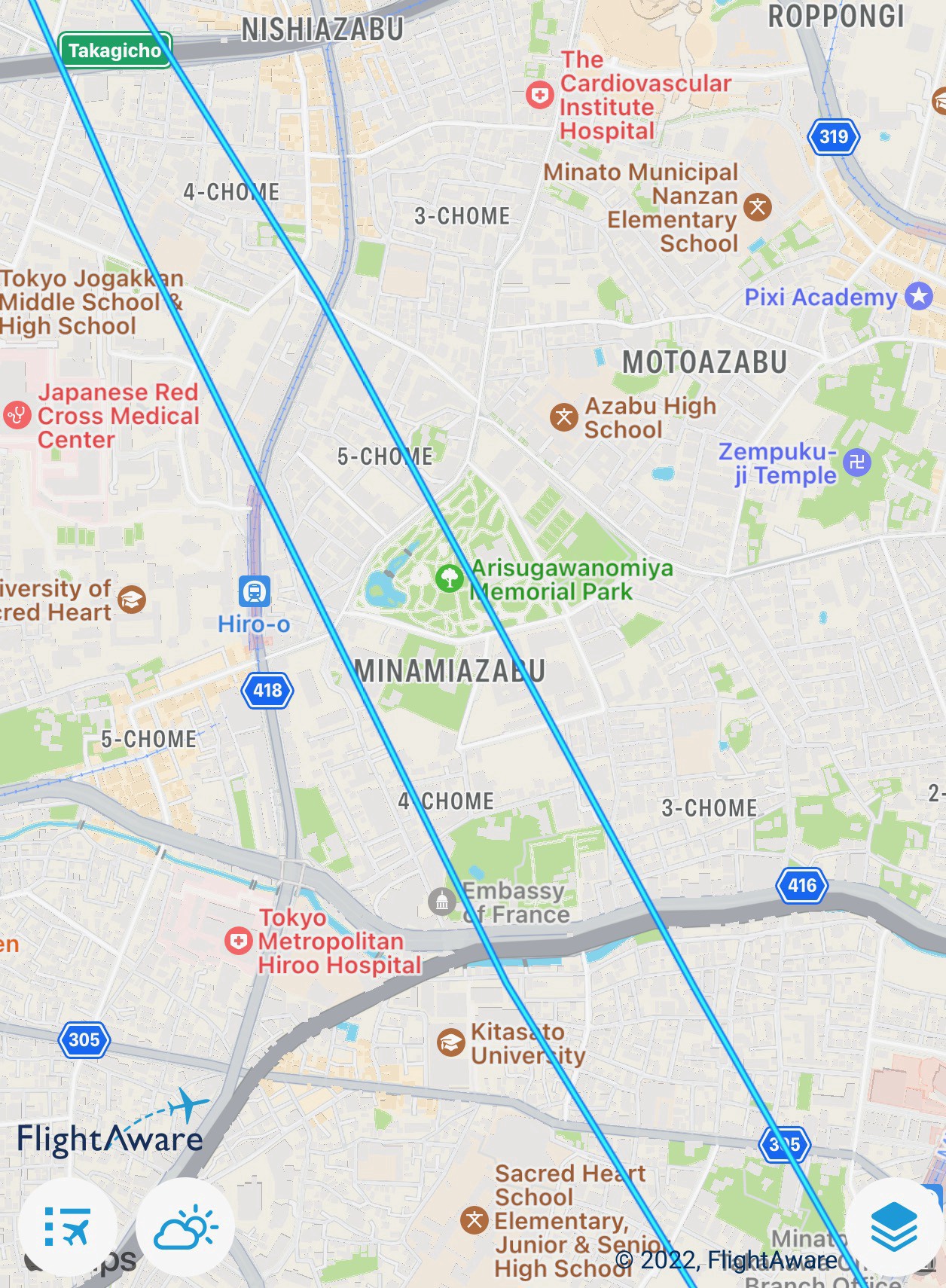

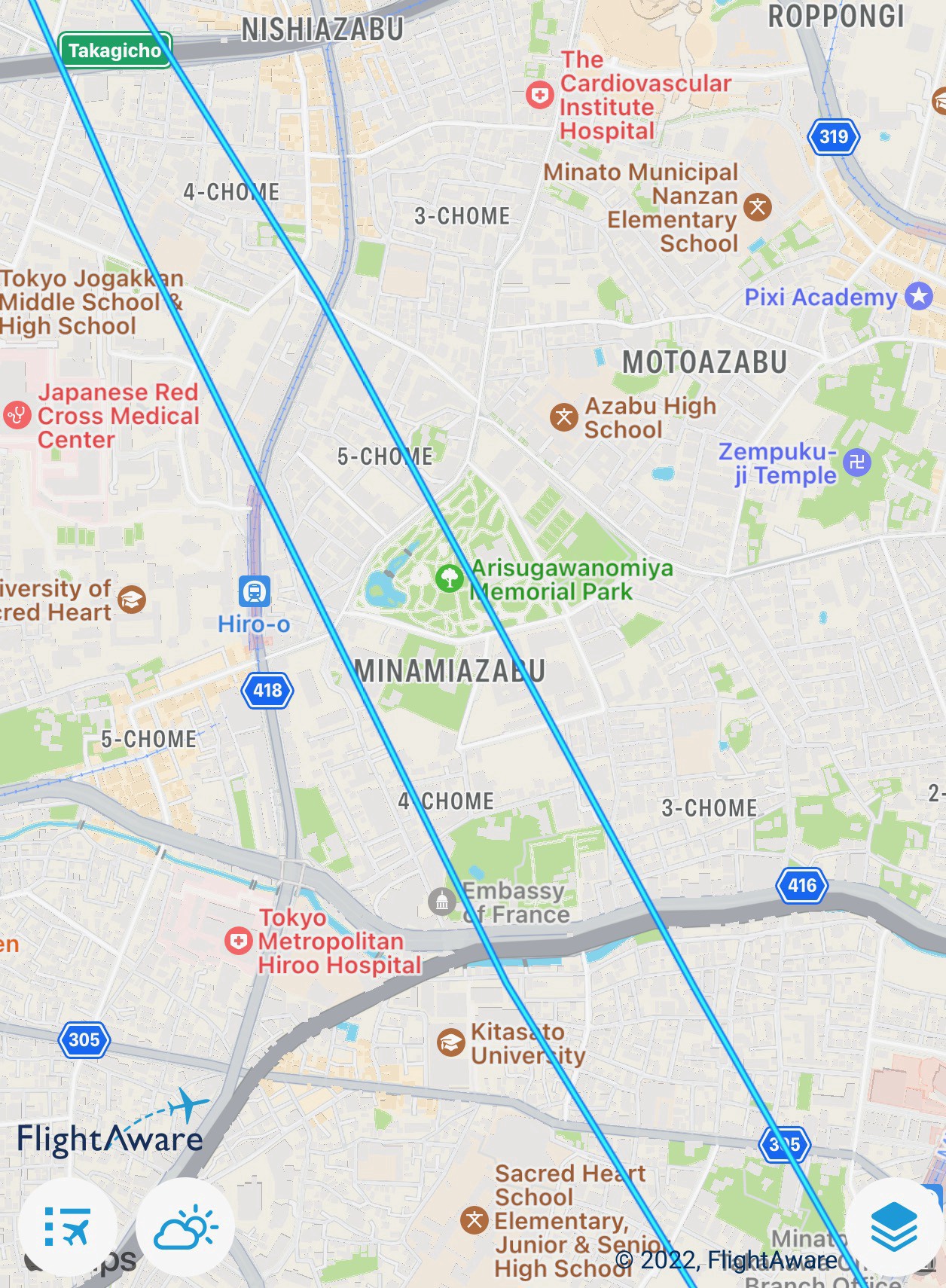

Low altitude approach paths directly over Tokyo’s Minami-Azabu’s branded wards and Arisugawa Park, located at the center of the map above. (FlightAware)

Here to stay

The western approach paths have been in operation only since March 2020, and were ostensibly created to expand the capacity of Tokyo International Airport at Haneda to accommodate the anticipated flood of arrivals for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. A sad irony is that the onset of the Covid pandemic prohibited foreign tourist arrivals for the Olympics, effectively rendering issues raised by the new western approaches moot.

Japan is gradually opening again however, and operations at Haneda have at the time of this writing already seen a noticeable uptick in foreign arrivals. While much of the airline traffic is domestic, (for which in Japan wide-body jets are commonly used), more and larger aircraft from international points of departure have begun to join the landing parade. This will only become more frequent as Covid-related restrictions on arrival quotas are lifted, and the volume of airline traffic nears the anticipated maximum of one every two minutes thundering down each of the two western approach corridors.

Given the substantial safety and environmental impacts of the new approaches on affected urban areas, a case could be made for their retirement. Certainly, the wealthy denizens of the neighborhoods below the approach paths, who include bankers and billionaires, major construction company owners and senior executives, well-placed individuals in government, and others of “high repute” would collectively have the makings of a powerful lobby group. Three problems here:

1. Collective activism, to say the least, is not particularly common (or effective even when the troops can be rallied) in Japanese society, especially against bureaucratic behemoths such as the MLIT.

2. The Covid pandemic will pass, and Japan will resume its imperative to boost its international tourism industry to meet ever-increasing foreign visitor targets (currently 60 million by 2030).

3. The new western landing approach paths are essential for this, and for justifying the vast investment made in Haneda’s Tokyo International Airport. This includes negotiation with the US military for dual-use airspace, newly expanded domestic and international terminal facilities, runway and taxiway physical and electronic expansion and upgrades, new ground as well as vehicle transportation infrastructure.

In short, the western ILS/LOC and RNAV approaches to runways 16 Left and Right over Tokyo’s branded neighborhoods are here to stay.

That leaves the only other malleable element in the equation: the socioeconomics of the underlying districts or wards. Given that most high-rise buildings are, by virtue of their construction somewhat immune to the environmental impacts of low flying aircraft, as are industrial and manufacturing plants, what is most likely to change in desirability, character and value is the more susceptible residential fabric and community infrastructure. Potentially, this means a downgrading of property prices in these branded neighborhoods as the reality of compromised environmental quality becomes more commonly known and understood.

Airliner on final approach over Shinagawa, with flaps, landing gear extended. Engine thrust (and noise) is increased to compensate for the extra drag. (Kotaro Ebara)

From branded to banal?

The adage “location, location, location” refers to geographic desirability, which is universally a confluence of access to good schools, desirable amenities, same or higher socio-economic neighbors, high-quality bordering-on-exclusive open space, and pleasant built as well as natural environmental conditions. All of this coalesces in the catch-all notion of “image” or “brand”. Make no mistake, the neighborhoods mentioned above are “branded”. They are highly familiar to Tokyo’s real estate industry and are quintessentially aspirational for up-scale, would-be home buyers.

For now.

Students of urban history know many examples of such neighborhoods that have undergone tectonic transformations, with external forces accelerating complete downshifts in desirability (for the higher social echelons) and their eventual replacement with a very different socio-economic class. Value can be driven up or down depending on the forces at play.

Arguably, the cacophony of roof-skimming jumbo jets, depositing clouds of noise and exhaust contrails at two-minute intervals for the best part of the day, seven days a week, 52 weeks per year may well be one of those downgrading forces.

It is early days still. Japan as a country, its institutions, and its real estate industry (with its often-unfathomable logic) may well retain the famous momentum that makes this society so stable and immutable. There may well be an “adjustment” that negates any significant impact on desirability of the affected neighborhoods or real estate values. What form this adjustment might take remains unclear. People adapt, expectations are lowered, glazing is tripled, earplugs are installed, and many of us now are accustomed to wearing face masks anyway.

Absent such “adjustment”, we are approaching the precipice edge of a tectonic shift in the way a significant slice of Tokyo’s prized urban fabric is seen and traded. Tokyo’s branded neighborhoods may already be on an irreversible collision course with fate, and in the embryonic stages of economic devolution that urban historians will ponder in the not-too-distant future.

NOTES

1. All altitudes are Above Ground Level (AGL) unless otherwise stated. International aviation convention expresses altitudes in feet (ft) and airspeed in miles.

2. Haneda’s “Runway 16 (Left or Right) ILS (Instrument Landing System) are “precision approaches” requiring strict (50 foot maximum deviation) vertical and horizontal adherence to a 3-degree glide-slope, with prescribed FAF (Final Approach Fix) entry point altitudes of 4000ft at 12.1miles from the Runway thresholds. In case the ILS equipment is unavailable, a LOC (Localizer) approach is used on the same glide path but with an entry (FAF) altitude that is 131ft lower.

3. “Test flights on new route over Tokyo lead to noise complaints”, The Asahi Shimbun, February 3, 2020

4. “[Noise] levels of 55 decibels outdoors and 45 decibels indoors are identified as preventing activity interference and annoyance. These levels of noise are considered those which will permit spoken conversation and other activities such as sleeping, working and recreation, which are part of the daily human condition.” https://archive.epa.gov/epa/aboutepa/epa-identifies-noise-levels-affecti...

5. “Steep landing flight over Tokyo a result of talks with U.S. forces”, The Asahi Shimbun, April 13, 2020. https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/13273975

6. “Serious Incident Boeing 747–4D7 HS-TGX, 11 April 2018”, Aviation Flight Safety Network. https://aviation-safety.net/wikibase/209441

7. “B747 passed within 200 meters of Tokyo Tower”, Aviation Flight Safety Network. https://news.aviation-safety.net/2004/10/18/b747-passed-within-200-meter...

8. The author was part of the urban design team, in 1996–7 at Johnson Fain Associates, commissioned to plan the next generation of growth for LAX (Los Angeles International Airport) and its environs.