Known as one of the great influencers of modern Japanese architecture, Kenzo Tange's buildings, teachings and ideas have left indelible marks across the Tokyo's cityscape, and across the world.

Born in Osaka, Tange spent his younger years in China and Shikoku before starting high school in Hiroshima, where he first discovered the works of Le Corbusier and decided to become an architect. His route was less than direct however, as he lacked the high grades needed to get into his top choice universities, but was eventually accepted into University of Tokyo's architecture department in 1935. He returned for postgraduate study and later became an assistant professor, opening the Tange Laboratory before becoming the professor of the Department of Urban Engineering. Gathering a collection of promising students over his years of teaching, it was no surprise some of the most leading names from the decade were his proteges.

Before this, however, he made numerous contributions himself to the architecture of Tokyo and Japan, recognized for his city-planning abilities and modern approach. Following the destruction of WWII, he was awarded first prize in the competition to design the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. His axis-structured design centered around an elevated, minimalist building designed to negate all distractions and focus the minds of visitors on its contents. The Peace Boulevard, which stretches out to the preserved Atomic Bomb Dome also features a moving cenotaph, which lists the names of all who lost their lives.

With a modern appearance but inspired by traditional ceremonial tombs from the Kofun Period, the memorial reflects Tange's unique ability to incorporate traditional Japanese elements into his works. This loyalty to traditional elements can be seen in the arched roof of the National Gymnasium designed for the 1964 Olympics. Housing the swimming and diving events, the sweeping shapes reflected water, but were undeniably reminiscent of elegant temples in silhouette. Although there were plans to refurbish the iconic designs, new stadiums will instead be built, but in a perfect legacy, they will be designed by Kengo Kuma. A fellow Pritzker Prize winner, Kuma was inspired to become an architect at the age of 10 when he first saw the stadiums designed by Tange, which were later declared to be "the birth of modern Japanese architecture" by leading architect Tadao Ando.

It was not only Ando who hailed Tange as the leader for modern design, however, and he soon became the by-name for modernism and closely related to the Metabolism movement specifically. Fumihiko Maki and Kisho Kurokawa, both his students, were leaders of the group and heavily influenced by Tange's designs and theories on not only architecture but urban planning as a whole. In 1961 Tange released his Plan for Tokyo in response to the incredible growth the city was undergoing at the time.

Rather than simply expanding out as traditional thought would allow, he aimed to restructure the city, using linear inter-locking loops spreading out across the bay. Focusing on satellite cities and decentralization, the design reflected his belief that the rising popularity of cars would be a game-changer in relation to people's concepts of space. Focusing on transport connections and reflecting his underlying preference for axis-based design, the clean and structured yet expandable concept was an ideal never realised. So grand a proposal, however, was likely a symbolic rather than realistic one, although it had great influence on the growing Metabolist movement.

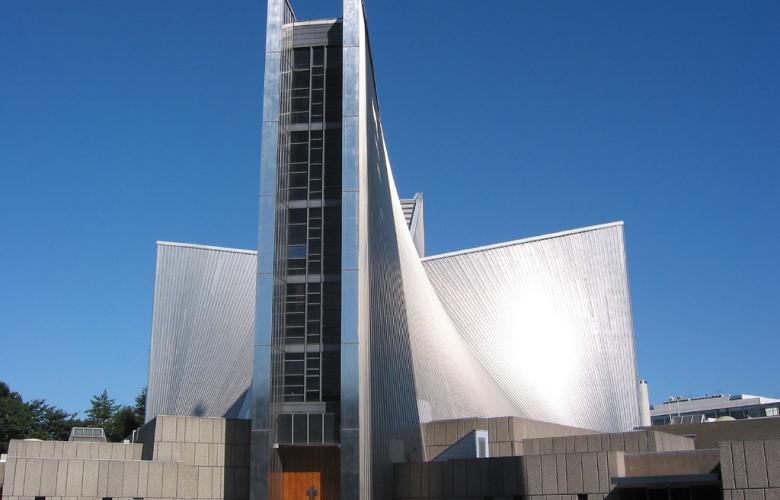

By considering both individual buildings and the city structures they would exist in, Tange moved from the spheres of architecture to urban design with ease, managing to be respected and groundbreaking in both. His most influential architectural feats in Japan include the Fuji TV Headquarters, The Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building and St Mary's Cathedral, all still standing today. Working on creative, governmental and religious buildings while maintaining his distinct style Tange again reflected his ability to adapt Brutalist styles with a softer element of design.

While St Mary's Church is a strikingly cold structure on initial impression, with bare concrete and stainless steel forming an imposing rectangular structure — it's inspiration is a little less harsh. Designed to represent the lightness of a bird's wings and featuring curves to reflect the force of the sky, it is a natural space in reality. Much as the traditional roots of his designs can be found in Hiroshima, it seems aspects of nature also run throughout his work if looked for hard enough. The natural element to the Metabolist movement can often be sidelined by the image of unforgiving concrete facades, removable steel elements and an unforgiving practicality which spearheads the designs. The original concept, however, of natural growth and evolutionary movement is a permanent presence.

While many attempts to imagine the future are quickly outdated and often ridiculed, Tange's visions remain relevant to Tokyo's image in the world today. While films such as the original Blade Runner may seem dated themselves now, the image of Tokyo they conveyed lingers on. Placed in contrast to neon backdrops and showing the decay of futuristic ideals, Metabolist buildings were inspirational in the designs for the film. More recently, the Wes Anderson's Isle of Dogs showcased a stop-motion city called Megasaki — a Tokyo-like metropolis with an ancient district remaining in the center. Paul Harrod, the animation director for the film studied the work of Tange when creating the cityscapes. Seeking an aesthetic that resembled the past's imaginings of the future, he appreciated the combination of Japanese design merged with modernity and sought the contrast of pre and post-war Japan.

Recognised across the world as a key designer of modern-day Tokyo, Tange's contributions to architecture and city planning are unlikely to be forgotten any time soon.

By Lily Crossley-Baxter

Similar to this:

Living in a material world: The creations of architect Kengo Kuma

The architects of success: Behind Tokyo's famous landmarks

Innovative, influential and ingenious: Toyo Ito and his impact on Japanese architecture