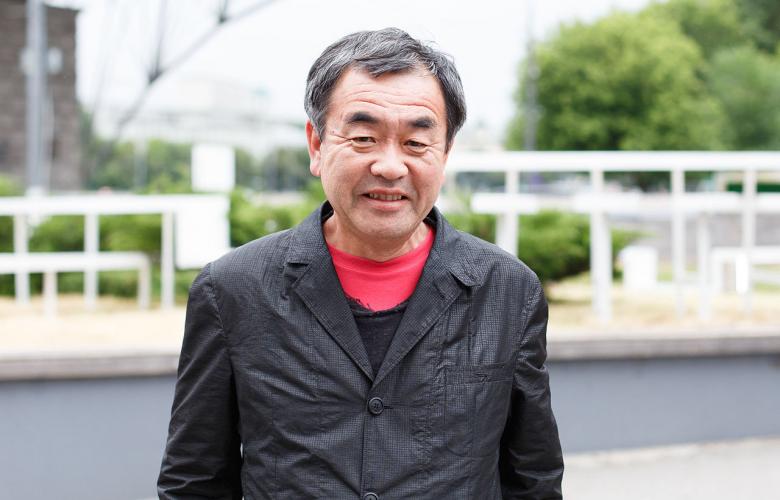

From the striking Asakusa Culture Tourist Center to the Suntory Museum of Art, renowned architect Kengo Kuma is a visible presence in Tokyo and further afield.

Born in Kanagawa in 1954, he went on to study architecture at the University of Tokyo after being inspired by the 1964 Olympic creations of Kengo Tange and hasn't looked back since. Now a lecturer at his alma mater and leader of the Kuma Lab — a research laboratory for students — he creates breathtaking designs across the world.

Having spent time in the US, he started his own architecture firm in 1990 and is also a prolific writer, focusing on the use of space and the relationship of architecture with nature as well as using traditional Japanese design in the 21st century. His most well-known text, Anti-Object: The Dissolution and Disintegration of Architecture, written in 2008, details the importance of projects working with their surroundings rather than attempting to dominate them.

This belief was strengthened following the devastating 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, which he believes highlighted the "arrogance of designers and engineers" who thought "architecture was much stronger than nature." Following the confirmation that architecture was and always would be weaker than nature, he chose to embrace this and focus on natural materials, techniques and forms for his future creations.

This focus is clear when viewing his work (especially the post-2011 pieces), as he utilizes a varied selection of materials depending on the surroundings and purpose of the buildings he creates. Although his designs are visually impressive, it is the focus on material and modernization of tradition which truly makes Kuma's designs stand out from the crowd. Representations and reflections of the environment abound in his work, which he describes as a "frame of nature" combining the shapes and textures of the natural world, but in striking and modern forms.

Some of Kuma's most recognizable designs are formed from wood, including the Prostho Museum Research Center, the Yusuhara Wooden Bridge Museum and SunnyHills Japan. Wood has long been the staple of traditional Japanese architecture, something Kuma learned firsthand. Following the economic crash in the 90s, he left Tokyo to work in the countryside with local craftsmen, learning about the traditional and techniques used to build by hand.

Re-utilizing the skill of tsugite and embracing the flexibility of wood, he took inspiration not only from nature and the craftsmen who worked with it, but of the other roles of wood in Japanese society. The Prostho Museum Research Center is a mesh of wooden pieces measuring 6cm by 6cm which uses no glue and is based on a traditional toy from the Hida Takayama region of Japan. Despite these points of inspiration, the building is notably modern in appearance, with natural light and a strong visual impact on anyone who passes by. A style recreated at Sunny Hills Japan but with more of a free-form shape, the store in Omotesando takes inspiration from clouds and forests to create a warm space, as welcoming as it is intriguing.

Stylistically different but also using shapes from nature, the La Kagu open area in Kaguarazaka is styled after layers of earth and is reminiscent of the Senmaida rice fields, terraced on the hills of Japan's agricultural areas. The wooden steps double as seats, creating an area for rest as well as movement — highlighting the dual purpose of architecture as it responds to the needs of the community, much as natural materials do.

While a common theme, wood is not the only material used to reflect nature in Kuma's designs, with stone offering an often unappreciated bridge between nature and human design. The Stone Museum in Tochigi houses a range of works made from stone and, thanks to Kuma, is constucted from it too. Using 80-year-old stone buildings which were originally rice warehouses and traditional Ashino stone to create the joins between the old and new sections, the theme is continuous and all enveloping. Following Kuma's focus on light and transparency, there are semi-open buildings which serve as pathways between the three primary warehouses, relieving those who enter of the dark, suffocating atmosphere one could readily associate with stone warehouses. To further alleviate this, horizontal stone pieces were layered allowing natural light to enter, while still maintaining a robust and eye-catching structure which combines tradition and modernity in one swift glance.

Glass and its natural counterpart, water, are two additional elements used by Kuma to both reflect the natural beauty of surroundings and to help his creations merge seamlessly with them. In the US, Glass / Wood House could be easily missed by passersby in the forest in which it exists. Adding on to the pre-existing design of Joe Black Leigh, they created an L-shaped villa layered with wooden louvers to add intimacy to the isolation style of the original 1950s design.

Similarly, the Water / Glass House built in 1992 in Shizuoka merges seamlessly with the sea views thanks to floor-to-ceiling windows and layers of water which cover the outer surfaces. A prime example of Kuma's aforementioned desire to provide a frame of nature, the villa becomes part of its surroundings by embracing their natural qualities of reflection and light. The project drew inspiration from Bruno Taut's only Japanese project, the Hyuga Villa (which was itself inspired by the minimalist design of Katsura Imperial Villa), which offered views of Sagami Bay as the focal point of the house.

While Kuma's design preferences certainly turned a corner in 2011, the reflection of nature has been present in his work long before then, and reflects his true appreciation of the natural structures. Although past projects have focused on man-made materials like Plastic House (Tokyo, 2002), these are the exceptions, with light, transparency and nature at the forefront of his designs.

By Lily Crossley-Baxter

Similar to this:

Against the onslaught: Florian Busch on Tokyo's architectural ecosystem

Innovative, influential and ingenious: Toyo Ito and his impact on Japanese architecture

Tokyo: Capital of modern Japanese architecture