Designing cultural centres, libraries and some of the world's most unusual homes, Florian Busch is an architect in high demand in Japan and across the world. The architectural scene of Tokyo, however, continues to draw him in, although its limitations are as myriad as its opportunities.

Doing his best to transform challenges into avenues of creative design, and forever looking for the logic in the "charmingly weird" requests he receives, Busch has sought to remedy the issues faced by many who strive for something different in a traditionally conformist society. We sat down with him to talk about Tokyo's unique architectural ecosystem.

Finding the balance: House in Takadanobaba

The inventive nature of Busch's design highlights the need for a balance between vision and 'livability' in the capital city. While houses admired for their origami-like structure, internal gardens and narrow widths are impressive to look at, we asked the question on everyone's lips: can such spaces really be habitable?

Discussing his eyecatching House in Takadanobaba project, Busch notes that the choice of location suggested the clients may have had a rather differentiated idea of livability to begin with.

"The creative process is all about responding to someone's very specific ideas of livability, which is the essence of residential architecture - and very subjective. A house should allow the people that inhabit it to live their uniqueness."

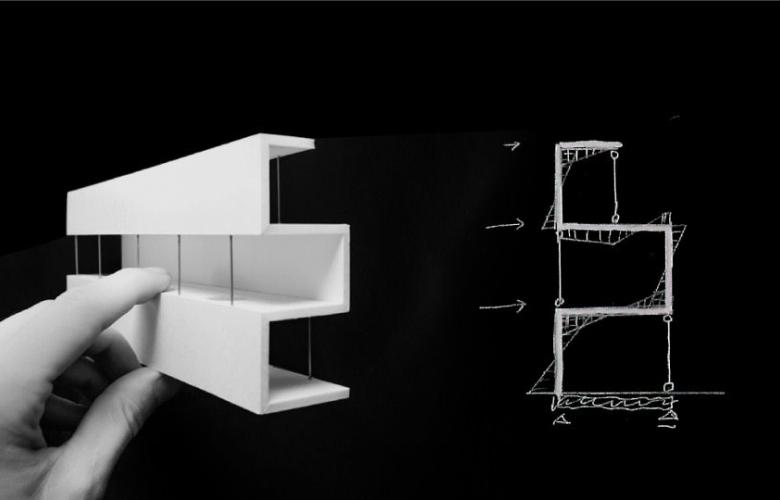

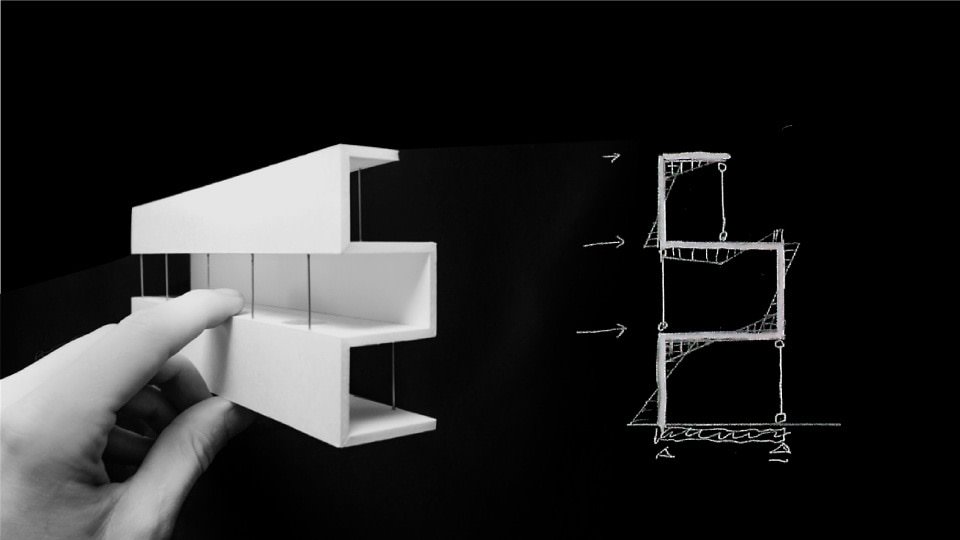

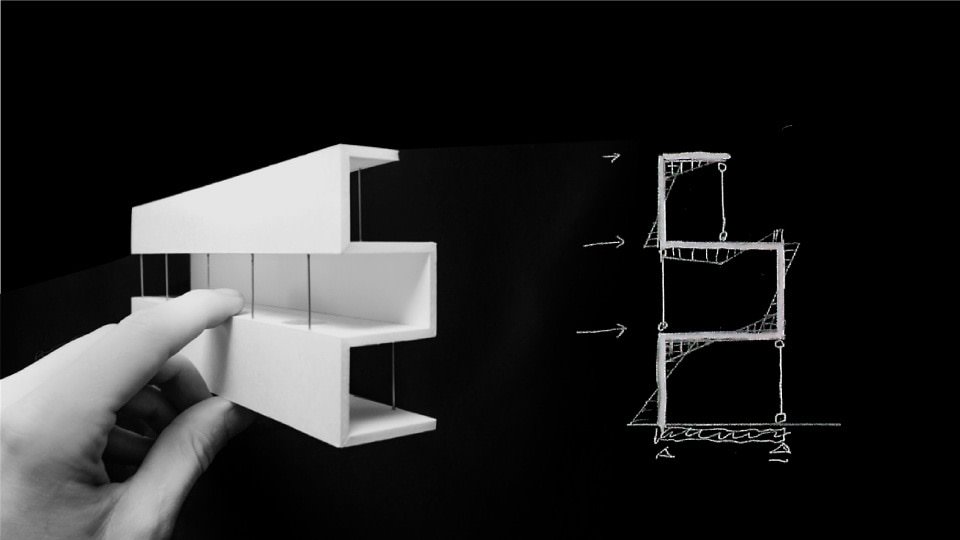

The property in question was a reaction to its setting: a narrow strip of land leftover between building sites, suitable only for a different kind of home. Working with a brief requesting generous spaces filled with light and air, Busch found that "the constraints of the site made such ideas seem so elusive that they immediately took on a very special meaning and expanded the possibilities."

Offering both a framework and challenge, the plot proved elemental in the end-design of the property. A fluid, folded structure was the result that emerged, with a lack of internal walls and the presence of seemingly open ends providing the light and air so key in the request.

In their description of this work, Busch's architectural firm uses the words of French philosopher Michel Foucault to reflect the inherent simplicity of the design: "The inside is nothing but a fold of the outside."

Room for expression in rebuilding

The freedom to indulge in the personal over the standard comes from Japan's distinctive building environment, in which family homes stand for an average of just 26 years before being demolished and replaced.

While this impermanence could be seen as a loss, it also releases people to create something purely for themselves, as Busch explains:

"When you know that the house is nothing more than a fashionable jacket, which you can dispose of (in the future) because your kids won't want to wear it, crazy things can be tried."

While these opportunities are available to a multitude of people, they are rarely seized. Instead, Tokyo is largely populated with homes which are, to put it politely, uninspiring. Taking the somewhat impolite and more creative route, Busch condemns the "detached houses which could have existed in the Truman Show" and recalls being driven through "an endless stretch of the usual pursuits of the theme 'home with a garden'".

It is not simply a Japanese tendency towards conformity which is to blame, though, as Busch believes many homeowners would opt for something different if it were more readily available, and costs would not be that disparate.

"The main culprit is, in my opinion, a conservative, profit-driven mass building industry, where any change is seen as a risk. The entire production line has been tailored for these houses; like a large oil tanker, it is extremely difficult, and can have expensive consequences, to its change course."

Rethinking green space: The House That Opens Up To Its Inside

Despite Japanese houses having a seemingly fixed pairing of indoor and outdoor space, however, one half of this concept is slowly being eroded. As land is carved out into neat plots stretching further and further from Tokyo, the battle for space is being fought between home and garden, with the latter often being sacrificed almost entirely.

With many properties filling the plots, the garden becomes nothing more than an "interstitial space of clutter" between houses. While architects are mainly concerned with the building itself, the neglect of the green space that traditionally accompanies it bothers Busch greatly:

"Under the illusion of a 'garden', which invariably becomes a meager junk space, we are, on an insanely large scale, accepting the systematic destruction of the unbuilt environment."

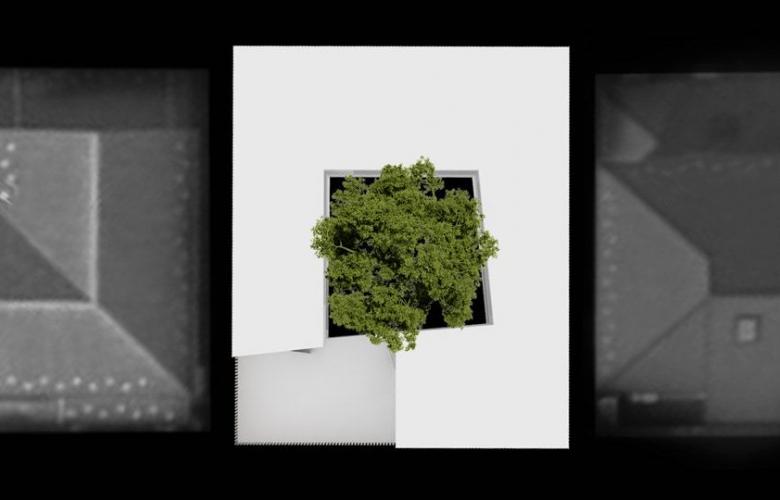

It was such a plot of regular suburban land that lead to the design of one of Busch's most innovative homes - The House That Opens Up To Its Inside.

Inverting the traditional form of a home and garden, a courtyard is cocooned within the walls, allowing light and privacy in equal measures. Although the plot was yet to be built around, the area was a "prototype for suburbia" and the future context of the home was easy to anticipate. Busch explains: "Instead of succumbing to the inevitable, the strategy was to shield against the exterior onslaught and focus inwards instead."

Thus, a house with a garden enclosed was created by building as close to the site boundaries as regulations allowed.

By rethinking the typical structure of the house and garden pairing, the focus moves from the outside world as it has come to be known - streets, neighbours, cars - to the outside world as it should perhaps be - natural cycles and seasons. Busch says that in the new home:

"Life revolves around this inner void, as views of the garden and the sky define the rhythm of the day and the seasons."

This concept is also visible in other projects such as Our Private Sky - a housing design that alters each property individually to ensure they have the optimum amount of light and air through a roof space, making "the sky the protagonist of everyday life".

Rather than a unique house alone in traditional suburbia, this project demonstrates the possibility of entire communities, each with a similar yet special home.

Looking forward: The possibilities of impermanence

Although not always fully exploited, Busch notes that the acceptance of impermanence is quintessentially Japanese, and the effect on Tokyo as a whole is awe inspiring:

"Tokyo's intensity and speed are that of a constantly changing organism. Pair that with the pragmatic lack of nostalgia, and you have the perfect driver's licence for an incredibly rapid evolution."

Compared to the slow-moving cities of the West, where "permanence is ingrained in the culture of architecture", Tokyo offers both "challenge and opportunity - design can adapt at a much quicker rate than elsewhere," says Busch.

While this ever-developing scene makes Tokyo one of the most exciting locations for an architect, allowing them to play "an active role in several cycles of evolution", Busch admits that there are concerns too: "Architectural education (here) just does not seem willing to adjust to a fundamentally changing building environment."

Busch believes promising young architects will appear in spite of this, however. As something of a mentor, he says he has no doubt that the next generations will surpass him and his generation - an evolutionary step to which he hopes he can contribute.

He recalls his own steep learning curve at the hands of Toyo Ito: "What left a huge impression on me was his youth and the admirable down-to-earth-ness with which he was able to communicate and channel energy into the teams, without imposing unshakeable ideas. Decades of experience had not satiated this wonderful hunger for the new."

Ito's impact is clear in the work of Busch, who was inspired by the Pritzker Architecture Prize winner's ability to take setbacks and use them to improve the end result.

The future of Tokyo is interwoven with and partly dependent on its architecture, as it will soon be facing the challenge of a substantially aging population, and a resulting shift in the real estate market, which Busch sees as inevitable. While the repurposing of buildings to absorb the usage changes would seem logical, he considers it unlikely, given Japan's history of transience.

Busch believes it is the architects of the future who provide hope and will determine the way forward:

"We are on the cusp of an era-defining revolution, and I think the new generation of architects is more equipped than ever to play a leading role."

By Lily Crossley-Baxter

Similar to this:

Florian Busch and the floating stadium: A futuristic Olympic insight

Technology, text and tradition: The architectural wonders of Japan's modern libraries

Out with the old, in with the new: Why older buildings are unpopular in Japan