Following destruction, regeneration offers an opportunity to create new environments for communities of survivors — and architects from Japan have lent their knowledge and skills to support these efforts. Temporary living following disasters comes in two stages: the emergency shelters which often lack privacy, and the homes which are built in the following months, often basic and small, but a home nonetheless.

In the immediate aftermath of a disaster, families are often left with no option but to remain in temporary living spaces created in school gymnasiums, community halls and sports centres. With crowded conditions and practically no privacy, the toll on mental and physical well-being is a grave concern. It was architects who devised the simple answer, transforming large, open halls into neatly divided spaces — returning order and privacy to those who needed it most. Shigeru Ban, a prominent disaster relief architect and humanitarian created a series of dividers from paper for the survivors of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake.

The earthquake was responsible for almost 16,000 deaths, the displacement of 200,000 people and damage to over a million buildings, and thus, the need for creative solutions was great. In the first movement of the temporary response, the partitions restored some semblance of privacy to those housed in open spaces for months. Designer Kazunari Fujimura developed a series of furniture pieces and dividers made of cardboard, moved by the sight of the distressed families having no way to store their few remaining possessions. Distributed to emergency shelters and temporary housing in Kesennuma, it transformed spaces into homes, with order and respect. The pieces used recycled cardboard, reflecting a trend in many projects to re-use the vast supply of materials generated by the destructive forces.

The construction of temporary housing spaces requires speed and efficiency, but also creativity as large numbers require housing in short spaces of time. Following the Great Hanshin Earthquake which left the city of Kobe mourning the loss of over 4,000 residents, Shigeru Ban aided the efforts. Using his unique Paper Log Houses, he provided housing for displaced in structures built from re-used easily recycled materials like beer crates, paper tubes and tenting material. Using sandbags in the beer crates as foundations, the structures had insulation layers of waterproof sponge and tarpaulin roofs. Later used in Turkey in 2000 and India in 2001, the structures cost less than USD 2,000 each and are a sustainable solution — easily built and easily repurposed when no longer required.

Following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, the need for housing was the inspiration for a series of projects by the country's architecture community, including Shigeru Ban and Toyo Ito. Moving to a more permanent structure concept, Ban designed a housing complex made of shipping containers in Ongawa — a town which lost 3,800 of its 4,500 homes. With 189 residential units stacked in sets of two or three floors, it allowed the area's limited flat building space to be maximized for occupancy. The design featured a checkerboard pattern which provided open air space and the use of pre-existing containers meant it was much quicker to complete and have excellent seismic performance — both important factors. As well as housing, the complex contained a community centre and market: a recognition of the need for a communal space, to allow people to work through the recovery together and return to a semblance of everyday life.

Another prominent architect who promoted the need for communal spaces following the disaster was fellow Pritzker Architecture Prize winner Toyo Ito. Visiting affected areas only days after the disaster, Ito formed a small coalition of architects to develop community spaces. Recognising the strength of the communities who had chosen to remain in their damaged hometowns, they wanted to provide spaces for them to use as needed. Along with Kazuyo Sejima, Riken Yamamoto, Hiroshi Naito and Kengo Kuma, the Home-For-All project was started, and 14 buildings have now been completed. Having transitioned the group into an NPO to help with costs and donations, it has successfully contributed to relief efforts in the more recent Kumamoto earthquake of 2016.

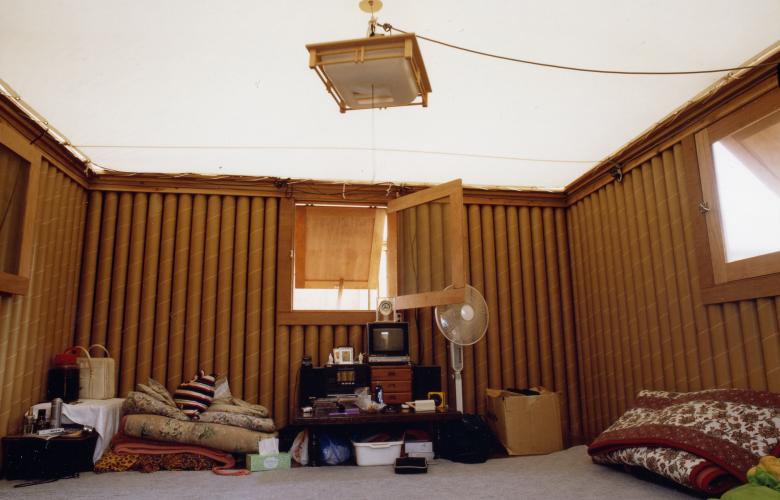

Intended to create a "base for those who lost their homes," no two buildings are the same, as each takes into account the specific needs and traditions of the local community it will serve. In Oya, a structure was built by the port to house fishermen on their breaks, waiting wives and a fish market. In Iwanuma, IT was the focus for re-starting the agricultural community, with a farmer's market and Skype area cohabitating in an airy, open space. The focus in Heita was on social gatherings, and a yurt-like space was created so locals could gather by the fireside to cook and drink together. As each project is treated as a unique opportunity, the community and environment are taken into account to ensure the needs of all are met, whatever they may be.

Klein Dytham's wooden lattice-roofed community centre in Soma was a particular architectural highlight, providing space for children who were unable to play outside due to radiation fears. By creating a space that felt like the outdoors, with plenty of light, a sun-hat inspired roof and tree-like pillars, it was a direct reflection of what the specific community needed at the time.

Putting out a call to children, students, and architects in Japan after the disaster, Ito's firm appealed for designs — and were duly inundated. Using them to create the winning pavilion at the Vienna Biennale in 2012, the project gained critical acclaim and the effort was increased. As people explored the possibilities of regeneration with a freedom rarely seen in countries without such disasters, the concepts of permanence and need were open to interpretation. Displayed on simple wooden plinths, the collection highlights Ito's feelings that mankind must not attempt to beat nature, but to work with it. His inclusion of wood in relief efforts is intended to provide softer, warm housing, as opposed to the cold provisions of metal structures.

With earthquakes an inescapable facet of life in Japan, building regulations mean that more and more buildings will survive future disasters, but it is small communities which will suffer the most. While architects continue to progress in creativity and sustainable design, their contributions can often be one of the most effective methods of supporting survivors as they look to the future.

By Lily Crossley-Baxter

Simiar to this: